Photo By Michael Alexander

Photo By Michael AlexanderAtlanta

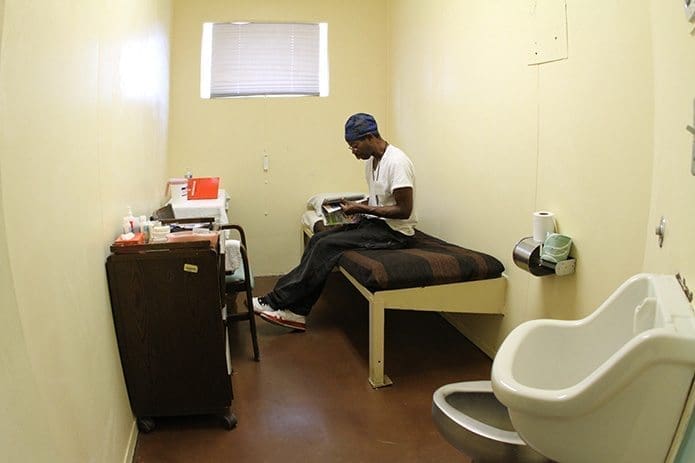

Jail cells transformed into Mercy units where ill homeless men recover

By NICHOLE GOLDEN, Staff Writer | Published November 27, 2014

ATLANTA—In the fall of 2012, Seth Weingarten was staying at the night shelter of the Atlanta Mission.

A diabetic, Weingarten was running out of the medicines he needed. During the day, he would sit along Luckie Street in downtown Atlanta.

“I didn’t feel lucky,” quipped Weingarten. “At the time my sugar was out of control. I was carrying everything on my shoulders.”

Then Mercy Care entered Weingarten’s life.

As the Connecticut native’s health declined, an Atlanta Mission staff member referred him to Mercy Care’s recuperative care unit.

The program, housed in the Gateway Center on Pryor Street in Atlanta, opened in 2010 and fills a critical gap in care for medically fragile homeless men. These men are sometimes outpatients or are ready to be discharged from hospital stays. Apart from this program, they have no place to go to recover.

“I was in and out of the hospital,” said Weingarten. “It was a great program. They help you get on your feet.”

At Mercy Care, Weingarten had a place to plug in his CPAP machine for sleep apnea and better monitor his cholesterol and hypertension, associated with diabetes.

Physical disabilities and dyslexia had contributed to Weingarten being unable to find enough work.

“I’d been in and out of shelters for five to seven years,” he explained.

Through Mercy Care and its resources, Weingarten was able to obtain permanent housing at Welcome House in Atlanta.

As a graduate of the recuperative care program, Weingarten comes back to volunteer by helping set up for classes or encouraging current clients.

Seth Weingarten participates in the Wednesday morning therapeutic art session at Gateway Center, Atlanta. Weingarten, a Connecticut native who struggled with dyslexia and a host of other health issues, was in and out of shelters for about seven years before coming to Mercy Care’s recuperative care program in the fall of 2012. Photo By Michael Alexander

Having worked in Connecticut as a janitor and driver, Weingarten says he is still willing to work to help others.

“Poverty … that’s a big word,” he said. “I don’t choose this.”

On a mid-November morning, Weingarten sat at a table covered with construction paper and pictures cut out of magazines. He was joining current Mercy Care clients in an art therapy class.

“I just became an uncle the third time around,” he said. “I’m making a card for my little niece.”

For the first time in years, Weingarten was set to visit family for Thanksgiving. “I’m leaving on the Greyhound,” he said. In early December, Weingarten will come back to Atlanta where he has a permanent roof over his head.

“I have my own room. That started here from Mercy Care,” he said. “I’m a thousand times better than I was.”

A path out of homelessness

Dana Washington is Mercy Care’s recuperative care coordinator and a registered nurse.

Washington, a former oncology nurse, came to work at Mercy Care about a year ago.

“This is my passion. I’ve done this type of work before,” she said.

The recuperative care unit has 19 beds. The men receive breakfast, a sack lunch and hot meal in the evenings.

The Gateway Center, once the Atlanta City Jail, is a central location for many agencies serving the homeless. Mercy Care also operates a health clinic and dispensary there. Mercy Care runs eight other fixed clinic locations throughout Atlanta and offers mobile health care services at five sites.

Men staying in the recuperative care unit sleep in rooms that were jail cells. Curtains are used for privacy instead of the heavy cell doors. Rooms that once imprisoned inmates now are the first step in having a more positive life.

Registered nurse Dana Washington is the recuperative care coordinator for Mercy Care at Gateway Center. The center provides programs and services for the homeless so they can eliminate their homeless status. Mercy Care is present to meet the medical and behavioral health services of the clients. Photo By Michael Alexander

Recuperative care residents stay between 35 to 40 days. While there, they explore obstacles to working or having stable housing, including mental health, substance abuse or family relationships that need repair. For a majority, this is a path out of homelessness.

“We get at least 65 to 68 percent housed or reunited with family,” said Washington.

While there, the men participate in mandatory group support sessions led by a resource specialist.

“That’s one of their agreements,” explained Washington.

Most of the clients are recently discharged from Grady, Saint Joseph’s or Piedmont hospitals.

“They need time to rest,” said Washington.

When a medically fragile person tries to recover on the streets, they often wind up back in the hospital. The recuperative care program prevents additional hospital stays and has cost benefits to the health care system.

“We’ve saved millions of dollars,” said Washington.

The staff works 12-hour shifts. The Gateway Center personnel and a “house man” from the unit supervise overnight. The men look out for one another, particularly for those with fragile mental health.

Washington said clients appreciate someone listening to them and the assistance in getting clothing and preparing for job interviews.

“Sometimes they just need some personal, one-on-one time,” said Washington.

The men also learn how to give back to others. Recent volunteer efforts included assembling hygiene kits at the Mercy Care Decatur Street Clinic for distribution to the homeless.

While there are serious issues to be addressed, the men also enjoy social activities. “We plan something fun for them once a month,” said Washington. Organizing picnics and parties helps the men learn how to budget.

Spiritual programs, led by a Catholic volunteer, are held each Monday. Washington said many of the men crave this type of support.

“We’re made like that,” said Washington about the clients’ spiritual hunger. “Even at their worst, they have hope.”

Washington believes Mercy Care is a good organization in that it provides the “whole gamut” of services.

Those who succeed help others

The Mercy Care Foundation, the fundraising arm of the health ministry, recently announced major campaigns to expand or improve on their programs, including launching a recuperative care unit for women and building a Mercy Care North center to serve primarily women, children and the elderly. While Mercy Care currently leases medical practice space on the north side, the new Chamblee property will be more accessible to public transportation and offer increased space for delivery of care. The project is estimated to cost $12 million.

“In January we will close on the property,” said Bonnie Hardage, Mercy Care Foundation president.

(Counterclockwise, foreground) Liza Kravets, a senior nursing student at Emory University, Atlanta, participates in the Wednesday morning therapeutic art session with Gateway Center residents Perry Middleton and Gyasi Phillips. Mercy Care has a clinic on the premises for treating the homeless men and women. Photo By Michael Alexander

The recuperative care clinic for women is to be located at City of Refuge in Atlanta, which would share costs. Mercy Care’s fundraising goal for purchase of furniture, fixtures, and unit equipment, patient assistance and staff salary at the women’s unit is $350,000.

“I see a growing need,” said Washington about impoverished women.

Dana Thompson is the resource specialist for the current recuperative care unit.

“Resource specialist is basically case management,” explained Thompson.

Often the clients coming to recover don’t have valid identification or other necessary documents.

Thompson does an initial assessment of the person’s mental health, financial state, and family concerns with one clear objective in mind.

“When they leave out of here, we do not want them to return to chronic homelessness,” he said.

Whether room at a shelter is located, or someone reconnects with family, or locates transitional housing, Thompson says that follow-up continues with program graduates for 120 days.

While staying on the unit, the men can begin substance abuse or mental health counseling.

Thompson enjoys his work and calls it payment enough to be able to show those who struggle a better way.

The ones who succeed return to help motivate others. “They come back and they shake their keys,” said Thompson, of the symbol of a place to call home. “They see hope again.”

Thompson leads group programs on topics ranging from personal growth, stress, coping and taking care of one’s self. Nursing students also come to work with the men. It’s difficult for the men when it’s time to leave.

“They do not want to go. We really show true concern,” he said.

Native Atlantan Horace Isom, two weeks into his recovery from serious digestive problems, said Mercy Care is an excellent program.

“It’s a big plus,” said Isom. He said the stress of sleeping in the elements caused his health problems.

“I had lost a job in 2011,” said Isom about being homeless.

He isn’t sure what’s next, but Isom does know that the recuperative care staff will help him figure that out.

‘I have a plan now’

Marshall Kendrick, who goes by his last name, thumbs through a Southern Living magazine with a homemade blueberry pie on the cover.

“It beats being out on the street laying flat on the ground,” he said about his recent admission to the recuperative care unit.

Kendrick was hospitalized due to breathing and heart problems and kidney failure. He knows “all the drinking and drugging” was to blame.

The personal trauma of witnessing the murder of a loved one led to homelessness and substance abuse for the Atlanta native.

“I was out for a while. My nephew had killed my mom,” said Kendrick. “Grady turned me on to this place.”

Now sober, and having survived drinking, Kendrick is sure of what to do.

“I have a plan now. Get me a new life and work,” he said.

At 52 years old, Kendrick says it’s time.

“I see it now. It shouldn’t have been that way. I can think better,” he said.

Relatives visited Kendrick in the hospital and he is hoping to reconnect with them. “I have a family out there,” he said.

Mercy Care is “all about unmet needs,” said Denise Garlow, the program’s marketing manager.

Mercy Care offers dental and vision care, HIV prevention and primary care, a nighttime street medicine program, and an increased focus on behavioral health needs of the homeless or underserved.

Mercy Care no longer has a direct connection with Saint Joseph’s Hospital following its 2012 merger with Emory Healthcare and therefore raises funds independently for its mission of serving Atlanta’s poor.

In 2013, Mercy Care served 12,796 clinic patients and 92 percent of them were uninsured. Eighty-three percent of the Mercy Care patients live at or below the federal poverty line.

In keeping with the legacy of the hospital founders, the Sisters of Mercy, Mercy Care’s work will be ongoing.

“It’s continuing and it’s growing,” said Hardage. “Our employees are angels on earth.”

To support the Mercy Care Foundation through a direct donation or to learn more about volunteering, visit www.mercyatlanta.org.