Photo by Bette Jean Taylor

Photo by Bette Jean TaylorAtlanta

Sudanese ‘Lost Boy’ in Atlanta hopes his story helps native country

By ANDREW NELSON, Staff Writer | Published October 30, 2014

ATLANTA—Majok Marier was tending to his family’s cattle herd when he heard the gunshots. Soldiers were attacking his family’s village. He fled. Along with tens of thousands of others who became known as the Lost Boys of Sudan, he for years evaded lions, fled gunmen, and found shelter beneath trees and nourishment from eating grass. He was 7.

Now a grown man, Marier has written about the life lessons he learned during his 14-year journey to America. Initially he penned the reflections to share them with the youth of Sudan, but after working with a former news reporter, they have been published as a book. He hopes his story of survival and perseverance will fund a nonprofit so water wells can be dug in his native land.

“Anything that can happen, good can come out of it. That’s why I have to write the book,” he said.

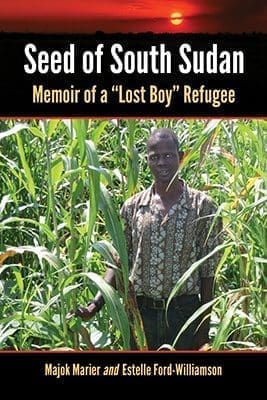

The book, “Seed of South Sudan: Memoir of a ‘Lost Boy’ Refugee,” came out in the spring before the recent release of “The Good Lie,” a film that places the story of the Lost Boys on the big screen. Marier applauded the movie for putting the experiences he and his friends lived through in front of audiences to raise awareness of their homeland. He was one of several Lost Boys interviewed before the screenplay was written.

In 2001, Marier was among the Lost Boys resettled in the United States. These young people, torn from their families, walked for months across three countries after being caught in a civil war between the Christian south and the Muslim north of Sudan.

Marier learned English in refugee camps. He became a Catholic there, too, as Italian nuns ministered among the youth. After nine years at Kenya’s Kakuma refugee camp, he received a ticket that would take him halfway across the globe. He arrived in Atlanta in February 2001.

“There was a lot of smoke coming out of their mouths,” he said about seeing people in chill winter air for the first time.

He settled in Clarkston and worked in the grocery business for a time, but now is a plumber’s apprentice.

By 2005, the violence that forced him to flee had lessened. He learned his mother had survived the ravages of war. Friends of his from Atlanta traveled to Sudan to reconnect with the families they had been forced to abandon. Marier couldn’t make the trip when his travel documents didn’t arrive in time. Instead, he wrote some 100 pages about his survival, and he asked his friends to share the story with the village youngsters.

He was moved to write his story so what happened to the Lost Boys of Sudan will not happen to others in the world.

“War is not good. It separates families. Some people die. And a lot of children can be suffering,” he said.

With a desire to do more for his community, he turned to a cherished friend of the Lost Boys, Gini Eagen, the pastoral associate at Corpus Christi Church, in Stone Mountain. For her compassion to them, Eagen is dear to the Sudanese men, who honor her by calling her “Mama Gini.” At one time nearly 100 Sudanese Catholics worshipped at special Masses organized by the parish in Clarkston, in walking distance of refugees’ apartments. Now they number about 50, as people have moved away for job and educational opportunities.

Estelle Ford-Williamson, left, helped Majok Marier tell his story of his experiences in “Seed of South Sudan: Memoir of a ‘Lost Boy’ Refugee.” Ford-Williamson, a former UPI wire services reporter, is a parishioner at Corpus Christi Church, Stone Mountain, as is Marier. Photo by Richard Willliamson

To help Marier tell his story, Eagen called on parishioner Estelle Ford-Williamson, a former UPI wire services reporter. The journalist found a foundation in his raw words to tell the saga tracing Marier’s steps from Sudan to Ethiopia to Kenya. Using the material and working together, the two crafted the book.

“He poured everything he could into the book,” said Ford-Williamson.

“There is a really deep story here. We talked a lot. We pulled a lot out. It took a good couple of years,” she said.

For his part, Marier had no trouble handing his work to his coauthor.

“It was easy for me because I trust Mama Gini. When she says something, I know it will turn out well,” said Marier, a lanky man of 34, a husband and a father of two.

His first trip to his country was 21 years after he fled. In 2011, he returned for his wedding and was there again in 2013. His wife and family live in Sudan, since he does not have the money to bring them here yet. He carries carefully wrapped photos of his youngest son, born in June, whom he hasn’t met.

While the writing took shape, Ford-Williamson, author of a book on Atlanta and editor of two civil rights memoirs, figured out how to get the book published. The response wasn’t good. The Arab Spring had grabbed the headlines when they started, not the troubled history of east Africa. Acting on a tip, they sent a chapter to North Carolina publisher McFarland & Co., which specializes in academic and nonfiction books. The story grabbed the editors’ attention. The 192-page paperback was published in May.

Ford-Williamson said the story’s theme is deeply human.

“With persistence and faith, (the Lost Boys) could overcome whatever they were dealing with. They could become strong, they could become educated,” she said.

In addition to Marier’s story, the book examines the current situation in South Sudan, a newly independent country in 2011. It considers the cultural customs of decision-making, the untapped oil resources, and the celebrities in Hollywood and professional sports who have shone a spotlight on the people of South Sudan.

The book’s purpose is to raise awareness and direct any proceeds from sales to pay for drinking water wells in Marier’s region in Rumbek, South Sudan. During his 2008 trip, he noticed women still walked miles daily to collect fresh water. The organization’s name is Wells for Hope. The goal is to raise $41,830 to construct three wells. Some $8,000 has been raised.

He and others hope to return to their homeland eventually with knowledge and skills to help South Sudan become a stable and self-sustaining nation.

“We have to go back and benefit our people,” Marier said.

To support the effort to drill wells for drinking water in South Sudan, visit wellsforhope.org.